Before we get back to the list, I want to tell you about my favorite game series!

|

|

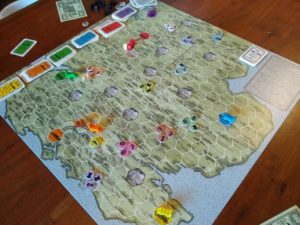

1830 (1986) and its descendants: One of the most divisive games around, 1830 is extremely long, bogged down with endless math and bookkeeping. The strategies are not straightforward, and the gameplay is utterly unforgiving. Most people find it boring or overbearing or just not particularly fun. But the people who do like this game LOVE it. On its face, this is a game about train companies building routes and making money, but that’s just the surface level. This is a game of leverage and liabilities, with players manipulating share prices, sabotaging routes, embezzling funds, and juggling capital equipment between companies to keep them afloat. Requiring both constructive and destructive play, 1830 rewards creativity and ruthlessness, perfectly fitting the rail baron theme. While never at the top of any best selling games list, 1830 has spawned many spinoffs with the same core gameplay, adding new rules and maps to give the experience its own unique flavor. There are over 100 of these titles, with my favorites being 1830 (Northeastern US), 1817 (Northeastern US again, but focusing on the stock market), 1849 (Sicily), 1880 (China), 18Mex (Mexico), 1844 (Switzerland), and 1848 (Australia). While I love these games and always find the first few hours exciting, these designs can sometimes show their age, and the last hour of the playtime can often feel like a chore as you grind through several rounds of income to find out who won. Certainly not for everyone, 1830 and its descendants are deep enough to keep you occupied for a lifetime.

|

|

10) Traders of Genoa (2001): There are a handful of pure negotiation games, but the one I find myself longing to play the most is Traders of Genoa. Instead of being about alliances and betrayal, Traders of Genoa focuses on short term deals. The game uses a unique system that gives each player equal time in control of the action. Being able to correctly value potential profit versus cold hard cash is a major key to success. With each player getting a turn holding the bulk of the leverage, everyone gets a chance to profit, but only the player who does so best will win. There is a random element in the game that is necessary to bring uncertainty and tension to the game but, unlike some negotiation games, it generally avoids swinging everything on a single card pull or roll of the dice. The productive flow of the game forces players to constantly make deals, as being stingy means being left behind. While some players just don’t like negotiation as a mechanic, if there is one negotiation game you will like, it’s probably Traders of Genoa, as it avoids many of the pitfalls of the genre and keeps everyone at the table constantly engaged.

|

|

9) A Game of Thrones (2003): Licensed games are often bad, relying on the popular brand to sell copies of a poor product, but there are definitely exceptions to this rule. A Game of Thrones is an unwieldy beast that demands a large player count, a huge chunk of time, and a big table. It also requires players to manage some unintuitive rules and bookkeeping. If you can put up with all of that, you get an amazing game that is true to its source material. With a plodding combat system and brutal caps on your army, making progress on your own is almost impossible, leading you to have to work together with others to make headway. However, only one player can win, meaning every alliance is based purely on self-centered need. And with the ingenious face down order system, betrayals happen at the worst possible moments, with dramatic results. People sometimes call this a negotiation game, but without any mechanics to enforce deals, the negotiations are an illusion. This is a game of brinkmanship and bluffing, a struggle where a player’s committed actions, not their empty words, are the true language of politics. A totally successful adaptation of the novels, you’ll need some stamina and a thick skin to fully enjoy this masterpiece.

|

|

8) Twilight Imperium (1997): Now in its 4th edition, Twilight Imperium is one of the most overwrought game designs ever. Armadas of plastic spaceships, mountains of tokens, a sea of tiles, and hundreds of cards are required to play this space opera simulator. Loaded with different units and upgrades that relate to combat, this looks like a tactical wargame at first glance, but it’s really a game of diplomacy, where military strength is the main bargaining chip. The amazing mechanic of promissory notes makes negotiations real by giving players ways to enforce long term deals. Too often deal making in these types of games boils down to meaningless fluff because the game doesn’t actually have any rules to bind the players, but Twilight Imperium gives agreements lasting consequences, predictable consequences that encourages players to work together. The amazing expansion brings the game to 24 factions, bringing the game delightful asymmetry for players to exploit. Tons of technology cards allow players the freedom to customize their strategy, but no matter which direction they head in, being able to understand the interests of the other players is going to be vital to success. The game gives numerous vectors of interaction to players, with trade, politics, and combat all being potential levers usable to get ahead of the competition. The ways players get points changes between every game, making flexibility key. Card pulls and dice rolls make chance an important factor, which can be disheartening is a game that takes as many hours as this one. However, if you can stomach the luck and have the time and table size for it, Twilight Imperium tells an epic story that is worth planning your day around.

|

|

|

7) Imperial (2006)/Imperial 2030 (2009): Imperialism is a terrible part of human history. Imperial doesn’t glorify it, instead placing its destructive greed in full view. Players in this game don’t play as the leaders of imperial powers looking to exploit the world. Instead, they play investors that manipulate those imperial powers to do what they want and make their investments worth more money. All of the surrounding countries are used as tools for the imperial powers to assert their strength, but in turn the imperial powers are just tools for the players to make a little cash. These powers can build armies, but if another player makes a larger investment than you, they can take control of that army and use it against your interests. The armies are expensive and the game uses deterministic combat, making all battles costly. In spite of the inevitable combats, this isn’t a wargame. The object isn’t to take over the world, just have the most money, whatever the state of the world is at the end.

|

|

6) Stephenson’s Rocket (1999): Stephenson’s Rocket starts out complex with tons of options available. Seven rail companies are strewn across a big map, waiting to connect the many cities and towns together. As tracks go down, players compete for three different types of majorities, being incentivized to build in different directions depending on where they place their stations and which cities they choose to invest in. When two rail companies meet, they merge, making one new, larger, more profitable company. Shares in these big companies are going to be worth a lot of money, but shares are also what you use to control which direction the railways grow. As the board starts to fill with stations and track, deciding when to spend your shares to veto your opponent’s decisions and when to accept their choices becomes a delicate balancing act. Let your opponent have too much control and their smaller investments will pay off too well, but sacrificing your share of the best company may be a price you can’t afford to pay. Stephenson’s Rocket is an incredible strategic experience that pits the need for long term planning against short term control.

Check back with us soon for the final five!